Newspapers—by virtue of the fact that their primary purpose is to report the news—tend to focus on the now, the narrow space of time that occupies the recent past up until the present. Newspapers like The Maroon, student newspapers, forget the past even more readily than other publications. With each graduating class, we lose a cache of information, histories, and wisdom. While this phenomenon presents challenges each time a new group of students has to relearn how to go to print, gain access to bank accounts, and generally keep the paper afloat, our short-term memory carries with it a much more insidious dimension: the illusion that each new year signifies a new start, a new canvas.

illusion that each new year signifies a new start, a new canvas.

The Maroon is 130 years old. We predate six U.S. states, both World Wars, and many civil rights. Our history winds through the histories of the South Side, Chicago, and the United States.

This article aims to trace The Maroon’s history, making the contours of our past permanently accessible. It’s essential to note, however, that this piece is an on-going project. Our history is far too long to fully capture it in one go, and history is constantly being made. Thus, it is essential that future Maroon editors add to this document as they read through the archives and discover more hidden histories.

A General History

In 1892—22 years after the Old University of Chicago burned to the ground—the Rockefeller-funded UChicago of today rose from its ashes. And with it, The U of C Weekly—today known as The Maroon— began. Founded by graduate students Emory Forster and Jack Durno in 1892, The Weekly printed short updates on sporting events, campus news, and student opinions.

While The Weekly was the only paper that found consistent success, another publication—The Daily Maroon—continued attempting to break into the spotlight, though with little success. The Weekly, which was supported by the University, consistently outperformed The Daily, leaving it in a state of constant struggle. By 1902, however, it was becoming increasingly clear that readers had a hunger for a daily publication. Herbert Fleming and Byron Moon—both students in the College—recognized this demand and came up with a solution: They proposed a merger between The Daily and The Weekly, which President William Rainey Harper agreed to as long as the resulting paper remained financially independent from the University.

The alumni association funded the new paper, allowing The Daily Maroon—now merged with The Weekly—to begin printing October 1 of 1902. The new paper was owned “by the entire student body” and relied on advertisement income to fund operations.

For 40 years, The Daily thrived as the premier UChicago newspaper, covering the University’s meteoric rise in the Big 10 Conference, its expansion into the South Side, and other campus news. Readers who brave the Maroon archives—which begin with the first issue of The Daily, October 1, 1902—will notice that while the paper does cover some news, the content is overwhelmingly centered around sports. In fact, The Daily dedicated page upon page to cheers, editorials and letters bashing other teams, and odes to the Maroons.

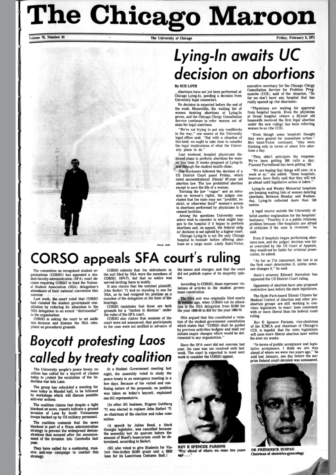

This jovial—albeit far from hard-hitting—energy persisted until World War II. In 1942, The Daily Maroon was forced to slow printing due to a dramatic loss of staff, changing its name to The Maroon. The draft meant that the paper was run mostly by women and men too young to serve. While The Maroon tried to print at least once per week, the staff struggled to keep the paper afloat, and there were consequently many weeks The Maroon failed to go to print.

Despite the immense struggles The Maroon faced, the women in charge transformed the paper from a sports rag into an essential source of news about the war. Articles t hat made it to print updated readers about students, professors, and South Siders out at war.

hat made it to print updated readers about students, professors, and South Siders out at war.

From the 1950s to the late 20th century, The Maroon took a sharp turn towards the political. Many UChicago students used the paper as a way to speak out against the war in Vietnam, critique President Ronald Reagan, and support communism. In fact, The Maroon became so leftist that editor-in-chief John Scalzi decided to create a separate, conservative publication called The Fourth Estate in 1989. The new publication existed under The Maroon brand but was focused on publishing conservative articles. Also during this period of hyper politics, The Grey City Journal was founded. It aimed to print liberal opinions and long-form reporting in a monthly, magazine-style format. Both The Fourth Estate and The Grey City Journal shut down operations in the late ’90s due to a lack of funding. However, Grey City saw occasional reprises throughout the years, and in 2018, soon-to-be managing editor Caroline Kubzansky resurrected Grey City as an integrated, long-form section of the paper.

In 1997, The Maroon published its first article online. Since then, The Maroon has maintained an online presence. The website has undergone many changes in the last three decades. In 2019, editor-in-chief Euirim Choi designed a bespoke website for the paper. In August 2022, The Maroon migrated to a new framework and created a mobile application, both hosted by SNO.

Printing Prejudice

The Maroon has a long history of sexism, racism, and abuse of South Siders. This history is visible in the very first editorial printed in The Daily Maroon.

While UChicago has been co-ed since its opening in 1892, the gender debate nevertheless persisted. In its debut editorial, The Daily Maroon wrote, “…the proposed separation of men and women students in the Junior College is without a doubt much the most important.” With the stage set, the editorial board then analyzes how various student demographics feel about the proposed change (though they fail to cite any data). They admit that most women seem to be against the change, arguing that they will lose out on the high-quality education they are guaranteed by being in the same classrooms as their male counterparts. With regards to how men feel about the change, the board writes, “In a general way a majority of men seem to favor the change. But in a jocose manner they say seriously: ‘If they don’t take the girls away from the University it will be all right [sic].’”

It’s important to note that The Daily Maroon leadership, at this point, was composed completely of men. The masthead had a designated section for “women editors,” who were responsible for editing content by women but not managing the paper. The two women editors at the time— “Miss Cornelia Smith and Miss Julia Hobbs”—were not part of the editorial board.

The editorial goes on to argue that women, despite their worries, actually stand to gain from a segregated Junior College, writing that, “Many a girl in the halls has listened almost with envy to another tell of a year at a woman’s college, and the delights of the college life of college girls together.”

For men, segregation promises “the virile life which comes from the camaraderie of manly men together, and the girls that charm and character from daily life with live, womanly young women….” While the grammar of this sentence is dizzying, the message is clear: The men of UChicago want their cake and to eat it too. A segregated College would allow men to experience the academically “virile” life of the College without having to give up their beloved “womanly young women.”

The board concludes that University administration ought to go forward with segregating the Junior College. Luckily, the University never chose to follow our advice to separate the Junior College by gender. Nevertheless, this first editorial set the stage for our checkered moral history. Women struggled for decades to secure a seat at the proverbial Maroon table. By the second World War, however, women were—by and large—running the paper.

During this same period, the racism baked into the paper began to surface almost daily. While covering the war, The Maroon routinely published articles using a common slur to refer to Japan and Japanese people. Writers and editors helped fuel the national hatefire used to justify Japanese internment camps.

Acquiring this information, unfortunately, didn’t require a deep dive into the archives; up until early 2022, two issues from the war hung prominently on a Maroon office wall, the slur displayed for all staffers to see. While the posters have since been removed, it’s clear that, even today, The Maroon struggles to cultivate an inclusive and equitable environment. This racism has been especially damaging for the Black and Brown South Side residents we cover.

In 2019, Maroon editors decided to publish a picture of Black minor arrested in a University building. Other members of The Maroon immediately called for the removal of the photo, arguing that, “The Maroon did a lot of damage—it opened up a young person and his family to harmful exposure, at no benefit to anyone else.”

While the photo was eventually removed, its publication sent a clear message to our readers: The Maroon still publishes prejudice and has a lot of work to do to earn the trust of its readers. Publishing the photo demonstrated a complete disregard for the individuals we cover. We leveraged a horrible moment in a young Black person’s life for clicks. We recognize that this aggression was not a simple aberration but the product of many institutional shortcomings, including a failure to create space for Black students on the paper, especially in leadership.

Of course, for all of the hate The Maroon has perpetuated, many writers, artists, and editors throughout its history have worked to transform the paper into an equitable platform, one that serves its communities, rather than tears them down. “Printing Prejudice” is not meant to undermine these peoples’ work or minimize the success they’ve had; instead, this section is meant to ensure that our failures are not forgotten.

It’s also essential to note that, while these vignettes of prejudice are undoubtedly exhausting, they are far from exhaustive. A mere hour perusing the Maroon archives will bring with it countless examples of racism and sexism. If you feel that a particular case of prejudice is missing from this section—which many surely are—please reach out, and we’ll do our best to document it.

Black, White, and RED all over: Communism, Espionage, and The Maroon

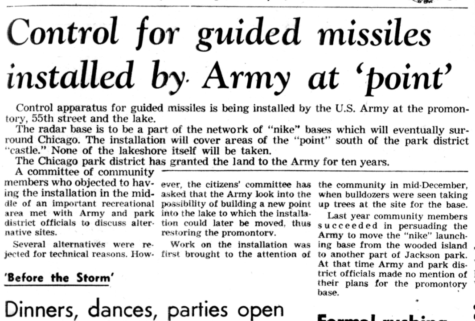

The University of Chicago is often thought of as conservative-leaning institution; after all, we’re the home of the Chicago Boys, Milton Friedman, and, more recently, Dorian Abbot. While the University undeniably produces influential, conservative thinkers, UChicago also boasts an equally leftist history—much of which, though underemphasized, is woven into the pages of The Maroon.

Over a decade ago, former Grey City editor James Hughes requested a document release from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Thanks to the Freedom of Information ACT (FOIA), the request resulted in over 2000 unsealed pages that confirmed that the FBI had “monitored the campus through informants at many levels of the administration and within the student body since at least 1944.”

During this epoch of federal intrigue—likely fueled by the Red Scare— Maroon editor-in-chief Alan Kimmel attended a Communist Youth festival in East Berlin. On October 4, 1951, Dean of Students Robert Strozier removed Kimmel from his position as editor, arguing that his attendance at the festival demonstrated his lack of “qualification to edit a free and independent newspaper.”

Along with ousting Kimmel, Strozier demanded that The Maroon cease production until a new editor could be elected. In a statement to the Board of Trustees, Strozier explained his decision to muzzle The Maroon: “Maroon management had drifted into the hands of a small self-perpetuating clique who, during the past two years, had used the paper as a means of expressing their political ideologies without regard to their responsibility to report the news competently and impartially.”

Along with ousting Kimmel, Strozier demanded that The Maroon cease production until a new editor could be elected. In a statement to the Board of Trustees, Strozier explained his decision to muzzle The Maroon: “Maroon management had drifted into the hands of a small self-perpetuating clique who, during the past two years, had used the paper as a means of expressing their political ideologies without regard to their responsibility to report the news competently and impartially.”

Editors subsequently voted 18–0 to continue printing despite the administration’s orders. They raised $200 in ads to fund the now-underground paper.

The Maroon was largely aware of the federal, anti-communist pressures at play. Former Maroon editor Jay Greenberg wrote an article about a decade after the Kimmel ordeal in which he details being tailed by the FBI. Danny Rubin, the Communist Party’s then-head of Youth affairs, had just given a speech at UChicago. Greenberg, who was driving Rubin to the El, noticed four unmarked cars, each filled with men holding two-way radios. The cars followed Rubin and Greenberg, but Greenberg “…led the agents on a convoluted chase through Hyde Park, circling in front of Harper Library and racing through the quads. Eventually he trapped the agents in an alley and confronted them. They refused to acknowledge their intentions.”

The FOIA later confirmed that the FBI had in fact been surveilling Rubin.

Gage Gramlick served as the editor-in-chief of The Maroon from March 2022 to March 2023.